Despite increases in workforce participation in recent decades, women continue to shoulder the majority of unpaid care in Australia. The economy and many Australian workplaces have been built around and uphold traditional, gendered divisions of paid and unpaid work. Paid work is more highly celebrated and the economic and social contribution of unpaid work is undervalued. This unpaid care is not just for children, but also aging parents, other family members and people with disability. Paid care work is also dominated by women and migrant workers – in part due to attitudes about women being 'natural carers' – and is also undervalued and often low paid and insecure.

Equality cannot be achieved without addressing who takes on, and who is expected to take on, caring responsibilities. Nor can it be achieved without valuing the substantial contribution unpaid and low paid care makes to families, the community and – notably – the Australian economy, which increasingly relies on paid and unpaid care and is facing care and support workforce shortages. This contribution is overwhelmingly powered by women.

Gender stereotypes and expectations contribute to the imbalance in caring responsibilities in families. These expectations can leave women feeling exhausted and guilty. Some women have greater caring responsibilities that stem from cultural, religious or community expectations. Men who want to take on more care may face difficulty or discrimination accessing leave or flexible work. This can stop men from sharing equally in caring and household responsibilities – and in the joy of family life. Here, kids also miss out on the benefits of having more engaged dads.Note 37

Gendered assumptions about parenting can also make it harder for same sex and gender non-binary parents to navigate care roles, parenting services and workplace entitlements and support.

The imbalance in unpaid care undermines women's lifelong economic security by limiting their participation in paid work and leadership roles. Women with caring responsibilities who want to work more hours can be prevented from doing so by lack of access to formal care and flexible work, and structural barriers like high effective marginal tax rates.

To achieve gender equality, unpaid and paid care responsibilities need to be more equally shared, and care needs to be valued and celebrated. The Government will prioritise policies that support families to make choices that work for them, and policy settings that don't entrench inequality.

See Data snapshot – unpaid and paid care for further analysis.

What have we heard?

'Despite women's work, both paid and unpaid, acting as the backbone of our economy during the COVID-19 pandemic, today women's work is still undervalued.'

What we'll do:

Australian Government actions

The Australian Government is committed to helping families balance caring responsibilities and juggle work and care, and to value unpaid and paid care and support work in Australia.

Actions underway

To drive action to share and value care, the Government has already made a number of investments and reforms. The Government has:

- committed to making the Government's Paid Parental Leave Scheme longer, more flexible, accessible and gender equitable, sending a strong signal that both parents play a role in caring for their children

- strengthened rights to access unpaid parental leave and flexible work, and made breastfeeding a protected attribute through reforms to the Fair Work Act 2009

- improved affordability of early childhood education and care through the Cheaper Child Care reforms; invested in childcare accessibility for First Nations families; initiated the Early Years Strategy 2024–34 to focus on the development and wellbeing of children in their early years; tasked the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) with an inquiry into the cost of child care and the Productivity Commission with an inquiry into early childhood education and care, charting a course towards universal access

- established an expert panel in the Fair Work Commission to help address low wages and workplace conditions faced in the care and community sector

- supported and funded an uplift in wages for aged care workers, and implemented skills and training initiatives to increase the diversity and profile of the aged care workforce.

In addition, the Government will continue to:

- develop a National Carer Strategy to deliver a national agenda to support Australia's carers

- deliver the National Strategy for the Care and Support Economy, setting out a road map of actions to a sustainable and productive care and support economy that delivers quality care with decent jobs

- fund programs to build the confidence and engagement of men as caregivers.

Future directions

To further accelerate progress, directions for future effort include:

- ensuring Government programs, processes and resources do not reinforce gendered assumptions about caregiving

- evaluating the operation of the expanded Paid Parental Leave Scheme, including men's uptake of paid parental leave, and working with employers to expand employer provided paid parental leave and improve uptake

- exploring how social security settings (along with tax) can more comprehensively recognise the economic participation of those performing unpaid care

- responding to Productivity Commission and ACCC inquiries into early childhood education and care, to make it more affordable and accessible

- taking action to attract and retain workers, including men, in the care and support economy

- exploring options to ensure there are not financial disincentives for students pursuing qualifications to enter professions and occupations in care and support

- considering how best to regulate migration for lower paid workers with essential skills in the paid care and support economy.

What others can do:

action outside of government

All people can consider how their own attitudes about care impact their choices, judgements and opportunities. The way care and unpaid work responsibilities are shared within families is a decision for individual households, but is upheld by – and can influence – gender stereotypes and expectations. Within households, families can have conversations about how work is split at home and recognise that paid and unpaid work both contribute to the household. Equally, families can consider early childhood education and care as a household cost, not a trade off against one parents' wage. Families can also challenge gendered assumptions about 'natural caring' ability, request flexibility from employers and access community resources and education around parenting. When allocating chores to children, parents can make sure these are not allocated on gender lines and that boys and girls are taught household skills and get equal pocket money.

Employers can go beyond their minimum obligations and attract the best talent by transforming workplaces into great, flexible places for parents and carers to work. They can support men to take a more equitable share of parenting and unpaid care by encouraging use of flexible or part-time hours and parental leave. They can also ensure that working flexibly is not a barrier to promotion or leadership by supporting flexible arrangements in leadership roles and promoting workers with a history of working part-time and taking breaks to care. Many employers are using paid parental leave and flexible work to attract and retain workers. Increasingly, this means not distinguishing between 'primary' and 'secondary' carers, and paying superannuation on parental leave. The Workplace Gender Equality Agency has resources to support gender best practice by employers.Note 39

The media and entertainment industry can challenge stereotypes through authentic and diverse representations of parenting and caregiving in the content they produce.

What structural change looks like: valuing and sharing care

Governments and employers play a role in better valuing and sharing care through the design of their paid parental leave schemes, especially in ways that encourage men to take leave and that minimise the long-term impact on women who take leave.

The Government's Paid Parental Leave Scheme provides a minimum entitlement that employers can build on. The Government is modernising and expanding the scheme through a range of reforms that aim to make the leave more accessible and flexible, encourage men to take leave and provide more support for caring.

To reinforce the value placed on caring, key reforms include expanding the number of weeks available from 20 weeks per family in 2023 to 26 weeks per family by 2026. From 1 July 2025, the Government will also pay superannuation on its Paid Parental Leave Scheme to signal that taking time out of paid work to care for children is a normal part of working life for both parents; help normalise parental leave as a workplace entitlement, like annual and sick leave; and reduce the impact of parental leave on retirement incomes.

To support sharing of care, the Government's scheme is now also gender neutral so that either – or both – parent can claim through the same scheme. The reforms introduce 'reserved leave' which means that from 1 July 2026, each parent will have 4 weeks of leave for their exclusive use, with the remaining 18 weeks available to be shared. Reserved leave encourages both parents to take leave, and sends a signal, especially to men, that their role as carers is valued. Other changes include expanding access to more parents with a family income limit of $350,000, which particularly benefits women who are the primary income earner in their family.

This combination of reforms is designed to support women's economic participation, signal that caring is valued and support men to take up a greater caring role. Employers are building on the Government's Scheme, with around 63% of Australian employers with 100 or more employees offering their own paid parental leave, with 33% of these offering paid parental leave regardless of gender, while 86% of employers who offer their own paid parental leave also pay superannuation on that leave.

As an employer, the Government has reviewed the Maternity Leave (Commonwealth Employees) Act 1973 and will introduce a range of changes to modernise the scheme and make it more gender equitable. In parallel, the Australian Public Service through its enterprise agreements is phasing in a consistent 18 weeks for both parents to be fully in place by February 2027.

How we'll measure progress

The Government will measure and report on the following ambitions and outcomes to demonstrate that change is happening.

Ambitions:

- Balance unpaid work.

- Close the gender pay gap.

Key outcomes:

- the unpaid work and care gap between women and men narrows

- parents and carers have access to affordable and high quality early childhood education and care services

- the gap between women and men working part-time or flexibly narrows

- the gender gap in use of and access to paid parental leave narrows

- men's representation in the care and support workforce increases.

Equality cannot be achieved without addressing who takes on, and who is expected to take on, caring responsibilities.

Data snapshot – unpaid and paid care

Women spend 9 hours a week more than men on unpaid work and care, and 83% of one parent families are single mothers.Note 40 For some First Nations women, caring responsibilities extend to protecting and caring for Country, which remains an important part of daily life and practice.Note 41

Unpaid care and support work impacts economic security, including the gender pay gap, with one-third of the pay gap attributed to the time spent caring for family and interruptions in full-time employment.Note 42

- In 2022–23, 35.7% of women and 7.3% of men who did not work full-time and wanted a job or preferred to work more hours reported the main reason they were unable to start work was 'caring for children'. This was higher for mothers with children under 15 years old (75%).Note 43

- Only 14% of employer funded paid primary carer leave is taken by men.Note 44

- 61% of First Nations women provide support to someone living outside of their household and two-thirds of these women also live in a household with dependent children.Note 45 First Nations women with caring responsibilities are also more likely to be in culturally unsafe and unsupported employment, and have higher cultural loads.Note 46

- There are more than 235,000 young carers in Australia who provide unpaid care and support to family members or friends who have a disability, mental illness, chronic condition, an alcohol or other drug issue or who are frail aged.Note 47

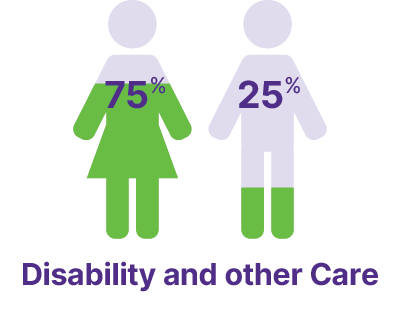

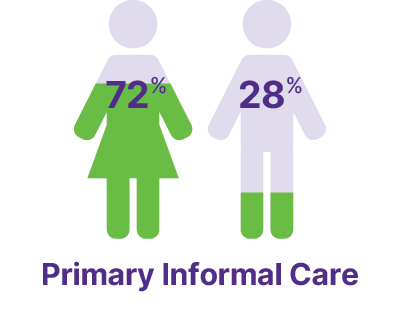

- Women make up 72% of primary carers to people with disability and older people,Note 48 and 35% of female primary carers have a disability themselves.Note 49

- Many men who take parental leave report discrimination when returning to work,Note 50 and those who access flexible work in the form of reduced hours experience higher levels of discrimination and/or harassment.Note 51

- For fathers, greater involvement in their children's lives increases ongoing participation in child care and other forms of unpaid work, heightens relationship satisfaction and enhances their ability to balance work and family commitments.Note 52

- For children, having an engaged and involved father increases the likelihood that the child will thrive across all areas of their life including their physical and mental health, self-esteem, educational outcomes and career prospects.Note 53

- Primary carers are nearly twice as likely to be in the lowest income quintile compared to non-carers (14.5% compared to 8.3%) and are also twice as likely to rely on the income support system compared to non-carers.Note 54

- Unpaid care work makes a substantial contribution to Australia's economy – estimated at the equivalent of 50.6% of the GDP.Note 55

Policy settings and systems create barriers to people with caring responsibilities participating in work.

- The loss or tapered reduction of Government support as income increases, along with taxation and childcare costs, can outweigh the financial benefit of a secondary earner returning to work or increasing hours after having children.Note 56

- For many working parents – particularly those based in rural, regional and remote areas, or working in shift or fly-in/fly-out roles – the limited accessibility of early childhood education and care impacts workforce participation.

- The Productivity Commission also found that 28% of Australian parents stayed out of the workforce to care for children in 2022, and they most commonly did so because the cost of early childhood education and care was too high.Note 57

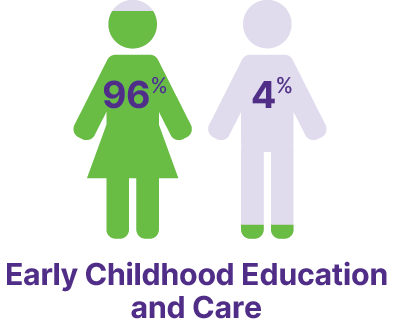

The paid care and support workforce remains female-dominated, undervalued and insecure – factors that are key drivers of the gender pay gap.Note 58 With people living longer and healthier lives, Australia will need more care and support services, and a larger workforce.Note 59

- It is estimated the care and support workforce will grow from around 657,200 to 801,700 workers by 2033. The demand for workers is likely to be higher than this – illustrating the importance of being able to attract workers of all genders to fill jobs.Note 61

- Migrants make up large portions of the care and support workforce, especially in aged care.Note 62 Healthcare and social assistance is also one of the most common industries of employment (16%) for working age First Nations people in 2021.Note 63

- An increasingly diverse Australian population will require a diverse workforce, as this enhances capability in meeting the varied needs of consumers.

Women continue to shoulder the majority of unpaid care in Australia.